So,You Want to Breed Poultry?

Defining your goals helps focus efforts for success

At some point in just about everyone’s poultry-raising career, the thought of breeding some birds and rearing their chicks enters the mind. For whatever reason, we think it would be great to put ourselves through the trials and tribulations of carrying out a successful breeding program. The process can be, at times, very frustrating but most agree the results are certainly worth it.

Before we get too deep into it, there are a couple of caveats:

- While the perspectives of other breeders have been cited and incorporated into this article, the bulk of the information has been garnered from experiences my wife Lisa and I have had over the past 50 years. What works for us (and the other breeders) may not work entirely for you.

- The intention of this article is to share basic breeding knowledge and in no way is intended to imply that winning show birds will be produced by utilizing the information.

Hatching chicks is a great family activity. It provides education for the kids, can instill a sense of responsibility in them, and chicks supply some downright funny entertainment. Watching them run around, explore. and interact with each other is fascinating. Each chick is different and watching them grow and develop their unique personalities is certainly interesting.

Define your goals

Some questions which will need to be answered before starting your program begin with this: What am I trying to accomplish?

Do you want to hatch from a specific breed you have or are planning to obtain, or do you not care about keeping the breed pure? If your goal is just to add to your flock, either is fine. This is a great way to get your feet wet. Keep in mind that the majority of us who now breed seriously started out with birds obtained from local hatcheries and it just mushroomed from there.

Additional questions include:

- Do I have the needed space and equipment?

- Am I going to hatch in an incubator or use broody females?

- Do I need a brooder?

- And last, the most difficult to answer: How many chicks am I going to hatch and safely handle with my current setup?

You will need to determine how many chicks you can handle safely. This is not an easy question to answer as we all have been known to get “chick fever,” the notion that we can hatch just a few more without any ill effects. We tend to forget that chicks grow and, depending on the breed, can grow rather quickly.

A long-range plan needs to be developed as to how the growing chicks will be housed, fed, watered, and kept warm.

Housing

If the goal is to produce some chicks without worrying about keeping your chosen breed pure, the housing piece is relatively easy. If the objective is to produce chicks from a specific breed, and you have more than one, you will need to separate them from the others.

Whichever is the plan, some basic rules need to be observed.

Your chicken coop or chicken house, whichever you call it, needs to be clean, comfy (for the birds), draft-free but ventilated. Provide as much natural light as possible. For those of us hatching in the winter and early spring, supplemental lighting is a necessity. Chickens require about 14 hours of light to get egg production started, with 16 hours being optimal.

Heat is not needed. In fact, winter heating can be detrimental to your birds. Chickens, just like us, adapt to the seasons. If you provide heat, then something happens to the heat source, (power failure, equipment failure, etc.) your birds will suffer and possibly die.

How you separate your birds based on breed depends on your setup and what breeds you are breeding and how many birds you intend to breed from. Large fowl or bantams? Are you breeding in pairs? Trios? Quads? Remember the comfy piece cited earlier: Enough room to move around, roosts, clean bedding, and a clean place for the female to lay her eggs are all integral parts of a successful breeding program.

Bedding preference seems to be a regional consideration with not all types—with the possible exception of shavings—available on a national level. Rice hulls, ground corn cobs, shavings, horse bedding are all used with success.

Absorbency and insulating qualities are the two biggest factors when selecting a bedding product.

Master Breeder Bruce Sherman offers these tips regarding housing and feeding:

- Bantams get about 5 sq. ft per bird and large fowl average about 8 sq. feet. Example: a 4x10 pen could handle 4-5 large fowl. Typically, our breeding pens are no larger than 3 females and 1 male.

- Raised nest box with clean shavings.

- Pens have roosts varying in distance from ground.

- Fresh water always and waterers cleaned weekly.

- Pens have plenty of ventilation and birds are let out often in fenced run for additional sunlight and exercise.

- We try to deworm prior to breeding and saving eggs.

Feed

There is nothing more controversial in the poultry world than the subject of feed. Next to the health of the breeders, feed is probably the most important thing to consider.

Feed the highest quality feed you can afford, keeping in mind that price does not always indicate quality. For us, a feed containing 18% protein works well. We also prefer a feed which contains animal protein, as chickens are, after all, omnivores.

Don’t forget the grit and oyster shell! Oyster shell provides a calcium boost and grit assists in digestion.

Some are of the opinion that if you feed a commercially-prepared pellet or crumble feed, grit is not needed, but we have found that birds offered grit do far better regardless of the feed type.

Incubator or broody?

When making this determination, consider the following; Some breeds are better mothers than others. Some breeds are more inclined to go broody than others with some breeds not going broody at all.

If you plan to use broody hens (and I wouldn’t use pullets) do some research on your chosen breed as to their parenting capabilities. What season is it? It’s not the best idea to use broody hens in the middle of winter in the northeast, for example.

If hatching naturally, note that a hen needs to be in the broody mindset if this is going to work. She needs to be showing the signs of being broody. She will start hanging out at her nest longer, start lining it with her chest feathers, and will start to be more protective of the eggs in the nest. You cannot just plunk a hen in with some eggs and expect her to sit on them without her showing signs of broodiness.

Incubators are available in a wide range of prices and come with different options. Do your research and purchase the best one you can afford that meets your immediate needs. If all goes well, you will be purchasing another one before you know it.

Incubator management tips:

- If hatching artificially, collect the eggs often and store in a cool place (not in the fridge)—60 -65 degrees Fahrenheit seems to work best. Do not wash the eggs as this removes the egg’s protective coating, Discard those which are excessively dirty.

- Set eggs in batches. The batch size depends on the size of your incubator. Eggs need to be rotated several times a day. If your incubator is equipped with an automatic turner, this work is done for you. If not, this process is up to you. Eggs should be rotated at least three times per day. Placing an “X” or other mark on the egg will help with a point of reference for turning purposes.

- Write down the date you set the eggs. Chicken eggs take 21 days to hatch and after the 18th day, stop turning them.

Brooders

Utilizing an incubator means you will need a brooder. A brooder is a heated container designed to rear chicks in. There are commercial brooders available from poultry supply houses or you can design and make your own.

Basically, you need a box or some other type of container, a heat source, bedding, lighting, a feeder and a waterer.

On our farm, we utilize 3-foot totes available at any department store. Heat is provided by heat plates designed for use in a brooder which are available at any poultry supply house. We are not big fans of heat lamps as they can be dangerous. Lighting is supplied by small clip-on desk lamps, one for each brooder. Feed and water are provided in standard chick feeders and waterers. Bedding consists of shavings only. Some folks recommend starting chicks on newspaper or some other substrate, but we have found shavings work just fine.

Brooders should be located in an area free from drafts with a pretty consistent temperature. The ability of the chicks to get out from under the heat plate should also be taken into consideration. The heat plate should not span the entire length of the brooder container, and attention needs to be placed on the location of the waterer so as to not allow the heat plate to artificially heat the water.

Choosing breeders

This is the crux of the matter. We have developed our objective, determined the number of chicks we can handle, answered the natural or artificial incubation question, and have assembled the needed equipment. Enclosures are clean, fresh bedding is in place, they are well lit, and well ventilated. Looks like we are ready for the final piece, selecting and adding the breeders.

Whether you are hatching from an assortment of your breeds or a specific breed, there are a few guidelines which should be followed:

- Try to breed from birds that are not too closely related. Brother/sister matings are the least desirable unless this is all you have. If the breeders you are using came from a hatchery as chicks, there is really no way of knowing how closely related they are.

- Only breed from robust, healthy, active, birds. Treat for lice/mites, as suggested above, and this would be a good time to worm. Note hens used for hatching are susceptible to lice/mites as they really do not get off the nest for long and are not interested in dust baths, etc.

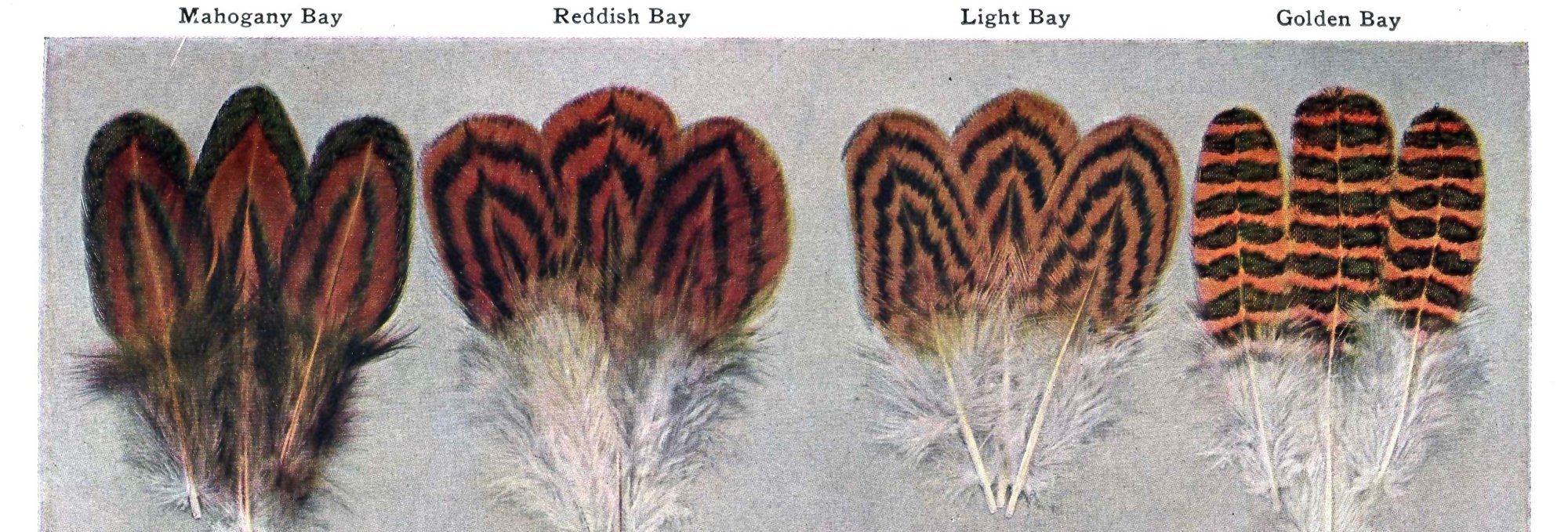

Breeding to the Standard

If you have set your goals high and wish to breed toward the American Standard of Perfection, noted breeder and APA judge Jonathan Patterson offers the following advice:

“The most important attribute for my consideration of a breeder bird is TYPE! I want to start with a bird that meets the Standard of Perfection description as closely as possible. That being said, I would also like to know a little background on that bird. What do its parents look like? Are its siblings comparable in size, type, and structure? This will tell me what I can expect from this bird’s progeny. While analyzing type, I also look for vigor, bone, feather quality, and reproductive ability. “

He continues:

“It has been written that the Standard description was written with the best productivity in mind. If the bird in question is a hen or pullet, I want it to lay well. If it is a male, I want to see evidence that he will be fertile. Overweight birds tend not to be good reproducers. Make sure to use the scale to see how close those breeders are to Standard weight. Using these criteria has worked well for me.”

Whatever the goal, breeding and raising poultry is a fun, enjoyable, sometimes frustrating, undertaking. Good luck, hatch what you can handle, and enjoy the results.

Tags:The Back Story

Chicken Whisperer is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.