Turkey Extravaganza

Turkeys converge on the Ohio National Show

In November of 2019 the American Poultry Association held its 146th Annual Meet, hosted by the Ohio Poultry Breeders in Columbus, Ohio. Year after year, the Ohio National is consistently the largest show in the country. This show was not only one of the largest ever held, with more than 8,500 entries, but it also hosted the first ever Turkey Extravaganza.

The event became the largest turkey show to be held in North America in recent memory. A total of 184 turkeys were exhibited, 131 in the open show and 53 in the junior show. All eight Standard Bred Turkey varieties were represented at this show.

In addition, there were also three non-standard varieties exhibited. They were the Chocolate, the Buff and the Sweet Grass.

Judging all those turkeys

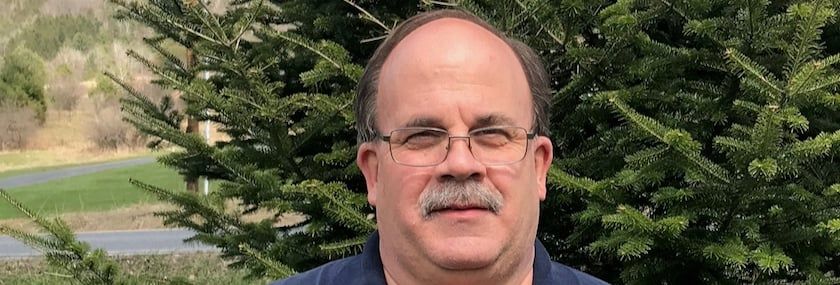

The larger shows may see 20 or 25 turkeys in a normal year, so you can see that this was going to be a massive undertaking, judging over 180 turkeys. It turned out to be an all-day job for Jeff Halbach, the American Poultry Association licensed judge who was chosen to judge this class.

To help simplify the judging and to appeal to the crowd that was watching, the birds were bench-judged. This is when the turkeys are placed on a table in small groups of 4 or 5 birds. They are examined, scored, and then returned to their cages to wait for final judging.

This method is much easier on the judge, who is required to handle every entry.

The judge needs to hold and handle every bird, to assess its shape and type, the most important aspects being judged. The judge is looking for the strength and breadth of the back, the abdominal capacity of the body, and the heart girth, all of which reflect the health, vigor, longevity, and production of the bird.

Body conformation is important in turkeys. The judge is looking for a body that is broad, round and has a full breast. This conformation gives the tom turkey a naturally stately appearance. Legs and shanks must be large, straight and well set. The head needs to be a good size. The judge will look each turkey in the eye, expecting a bold expression. Hens are similar to toms, but smaller, with finer bones.

Feather color and condition are also judged, as well as the turkey’s symmetry and carriage. Every bird on exhibit showed Star Quality.

Bench judging also gives the judge the opportunity to discuss the turkeys as they are being judged. Very large crowds surrounded the bench for most of the day. Exhibitors and visitors were excited to see this colorful display of turkeys.

And the winners are:

After the bench judging, the turkeys are returned to their cages. They are then examined again and placed 1st through 5th.

A Best of Variety (BV) and a Reserve of Variety (RV) are then picked from the top birds in each variety. Once all the Standard Bred Varieties have been judged, all the BV’s will compete for Best of Breed and Reserve of Breed. These two birds are the Champion Turkey and Reserve Champion Turkey, the two best Turkeys in the show.

The Champion Turkey can then compete for Best of Show along with all the other top birds in each classification throughout the show.

There were some quality birds in all the classes, but the Narragansetts and the Blacks were by far the best in the showroom that day. There were 23 Blacks shown, with excellent type and conformation throughout.

One of the Black Toms, which was exhibited by Christopher McCary,went on to be the Best Turkey of the show. The Narragansetts were the second largest class, with 14 birds shown. They also had great type and very good color. Johnathan Woodward owned the best of variety Narragansett, a hen that was also the Reserve Turkey of the show.

The other variety that really stood out that day was the Chocolates. Even though they are a non-standard variety and thus ineligible to compete for Best Turkey, they were strong in numbers with great type and very even color. This outstanding showing of Chocolates will greatly help the group of breeders who are attempting to qualify this variety for inclusion into the Standard in the future.

Turkeys in the Standard

Turkeys have been included in the American Standard of Perfection, the guidebook for all breeders, exhibitors and judges of all Standard Bred poultry, since it was first published by the American Poultry Association in 1874.

Five varieties of Turkeys were included in that first edition: the Bronze, the Narragansett, the White Holland, the Black and the Slate. Currently there are eight varieties in the Standard. The Bourbon Red was added in 1909, the Beltsville Small White in 1951 and the Royal Palm in 1977.

All the varieties of turkeys that are included in the Standard of Perfection fall into three basic weight categories. The Bronze and the White Holland are the heaviest, with the Old Toms (males) weighing 36 pounds and the Old Hens (females) about 20 pounds. The Bronze is not only one of the heaviest turkeys but it has also been one of the most popular varieties since its development sometime in the 1700’s.

The next group of turkeys has the Old Toms weighing 33 pounds and the Old Hens weighing 18 pounds. It includes the Black, the Slate, the Bourbon Red and the Narragansett. This group is very popular with backyard breeders and on small farms because of their size, the attractive plumage and their excellent meat quality.

The third group of the Standard varieties includes the Royal Palm and the Beltsville Small White. In this lighter weight class, the Old Toms weigh 21 pounds for the Beltsville and 22 pounds for the Royal Palm. The Old hens are 12 pounds for both of these varieties. The Beltsville Small White was developed in the 1930s to fill the consumer needs of the time. Many households wanted a bird that weighed only 8 to 15 pounds dressed but was still meaty, well finished, and free from dark pin feathers.

By the 1970s the Beltsville was replaced by the Broad Breasted White, a large commercial variety that, when slaughtered young, could fit the need for a smaller turkey. The Beltsville is not as popular today as it once was but is still raised by a few exhibition breeders. It has found a revival of interest in recent years with backyard breeders.

The Royal Palms, the most recent variety to be added to the current standard, are most striking with their solid white bodies with metallic black edges on the feathers. They are another variety that is very popular with backyard breeders.

Turkeys Have a Long, Long History

Turkeys evolved in North America nearly 20 million years ago. They have long been associated with festive dinners and celebrations, but some recent studies have shown that they were also used in religious rituals for hundreds of years. They were domesticated as long as 2,000 years ago by Native Americans, in the Southwest and in Mexico. Those people valued turkeys as food and for their cultural symbolic significance.

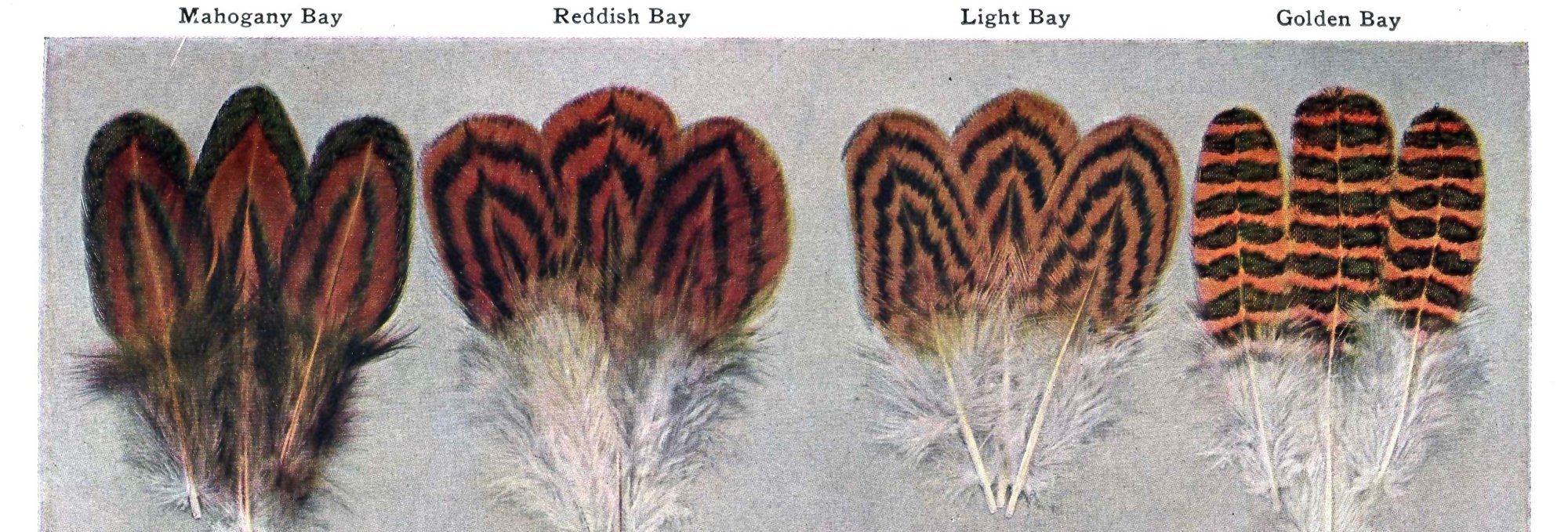

Color varieties are like branches on a bush, overlapping and sharing qualities but including the original wild colors.

All domestic turkeys are the same breed. The various color varieties were developed in the United States from the Wild Turkeys, which have in their genes all the possible colors.

The Aztecs called the turkey huexolotl, which sounds like a turkey’s gobble, and deified it as Chalchiuhtotolin, the Jeweled Bird. They raised turkeys as domesticated birds by the thousands. Turkeys held a place in many tribes’ mythology. Navajos told how Turkey (that’s its name) helped re-create the world after a flood. Turkey taught the Apache how to raise corn. Cherokees have tales about how the turkey got its wattles and why it gobbles. Santa Clara Pueblo and Zuni people explain why turkeys scatter when they hear humans with a tale of betrayal by the girl who kept them. The Tewa Pueblo Indians tell about it as a food source. Turkey feathers were used in ceremonies and to make feather robes and blankets.

The Emperor Montezuma and his court raised turkeys for their own consumption and to feed the carnivores and raptors in his zoo. W. H. Prescott in his “History of the Conquest of Mexico, Vol. 1, (1844) states that the court feasted on 8,000 turkeys during a single year.

When European settlers arrived in North America, wild turkeys were very abundant in the Eastern, Western and Southern parts of the United States and were also plentiful in Mexico. They are still found in very large numbers throughout North America to this day.

Turkeys were one of the riches European explorers brought back to their home countries. Turkeys became very popular in Europe. In a letter to his chief treasurer in the West Indies in 1511, King Ferdinand of Spain ordered every boat sailing back to Spain to include five male and five female turkeys, “so that they start a breed here.” They were enthusiastically received and soon were celebrated in heraldic crests as well as on the festive table.

The White Holland is a possible exception to the direct descent from wild turkeys. It is believed to have been developed in the Netherlands.

More popular

North American turkeys’ long history is documented in the APA Standard of Perfection. The Standard includes illustrations of the standard to which judges hold the birds they judge at shows.

Turkeys are more popular today than ever before. The turkey is America’s most famous fowl, and is raised and consumed in countries around the world. Since 1975 Americans’ consumption of turkey has increased dramatically from 8.3 pounds per person to nearly 16.5 pounds in 2019. The Turkey is truly America’s fowl.

Tags:The Back Story

Chicken Whisperer is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.