Judging Poultry

What is it all about?

You’ve observed poultry being judged at a show or fair. What is the judge looking for, and why? As you watch, you will begin to understand what the process involves.

Each judge has individual methods to follow in judging their assigned classes. Although each one’s preferences prevail, most judges follow something like this:

Each class (cock, hen, cockerel, pullet, old trio, young trio) is caged in a row. The clerk tells the judge exactly how many birds are entered in each class: e.g. four cocks, five hens, seven cockerels, nine pullets, two old trios and three young trios. This number varies with each variety within each breed. The American Poultry Association’s Standard of Perfection provides a full listing of all breeds and all varieties within each breed.

Most judges look over each class, walking back and forth perusing the birds involved: the entire breed, variety or section. The first glance gives a general assessment of the birds while they are reasonably calm. Once the judge begins handling each bird, those nearby will begin to tighten up and or get nervous, disturbing their natural stance.

Judging the breed

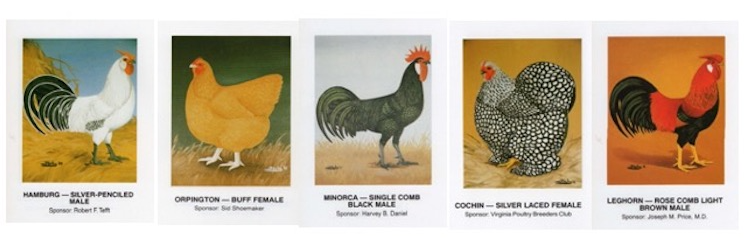

The natural stance or pose of the bird we call “type.” Type is difficult to describe, but it can be thought of as a silhouette, with each breed having its own silhouette.

Copyright Youth Exhibition Poultry Association. Used with permission of YEPA, all rights reserved.

Judges memorize the silhouette of each breed. They scrutinize each entry as to how it compares to that standard outline: body shape, tail angle, depth of body, shape of neck, comb and other head points, etc. The judge makes an initial decision to rank the birds as first, second, third, etc.

That initial decision changes when the judge handles each bird. As the bird is caught and removed from its cage, the judge discerns its weight, overall condition of its body, girth, depth and general feel of each entry. Feather condition can be a factor. More on that later.

After the judge has handled all the birds, he or she marks the placing on the entry card on each cage. When all the birds in each variety are judged and placings assigned, the judge will choose a best of variety (BV) and a reserve of variety (RV). When all the birds in each breed are judged, the BVs are judged against each other, selecting the best of breed (BB) and reserve of breed (RB).

Copyright American Poultry Association. Used with permission. All rights reserved

Judging the class

When the entire class has been judged and placed, the judge decides on best in class and reserve in class.

Large fowl are classed according to their place of origin (American, Mediterranean, English, etc.) and bantams are grouped according to their comb type and clean or feather legged. A large fowl class would provide, for example, a Best American Class and a Reserve American Class.

A bantam class might provide a Best Single Comb Clean Legged and a reserve Single Comb Clean Legged. These class winners are displayed in the center of the show on Champion Row.

Condition and cleanliness

The judge also assesses other qualities. Condition means more than the cleanliness of the bird. It refers to the bird’s body: weight, size, and overall health and vigor. A bird that is not in good condition in all these respects is better left at home.

It is imperative that every bird entered be clean. A bird that has hardened manure balls on its toenails or dirty feet will be quickly bypassed.

All birds should be washed and properly prepared for the show. Wash at least three days ahead of time so that the bird has time to dry and to preen its feathers.

Clip long toenails and the upper mandible of the beak on cocks and hens. Cockerels and pullets rarely need their toenails clipped. Clipping young birds may mislead the judge that the bird is older than it actually is.

Don’t spray your bird’s feathers or rub goo on its facial features (comb, wattles, etc.) that make it look abnormal. Small amounts of baby oil, or some other recipe, can make the bird look its best. Sticky sprays on the feathers are a distraction and can make the birds’ feathers gather dust.

A recipe that has always worked for me is half and half witch hazel and glycerin. Use it sparingly on the comb, wattles, ear lobes and even the shanks and toes.

Color variety

Each variety of a breed refers to the required color(s) of that variety. The APA Standard of Perfection illustrates a plethora of varieties within each breed. Some breeds have only one variety, such as Blue Andalusian, Australorp, and New Hampshire. Other breeds such as Old English Game have many varieties.

Written descriptions found in the Standard of Perfection must be read, studied ,and consulted in order to maintain the proper color(s) required within each breed. The color descriptions vary from breed to breed as well. Barred plumage, for instance, can take on various patterns depending upon the breed: Plymouth Rock, Campine, Dominique, etc.

Size and weight

Size and weight go hand in hand. Judges develop a “butcher’s hand” when determining the weight of each specimen. It may not be 100 percent accurate, but suffices to assess whether the bird is within the required weight parameters.

Some birds may appear too large but not exceed their allotted weight. Cochin bantams, for instance, may appear huge, but when handled, are more feathers than body weight.

A bird that is not up to weight and overall vigor will not be considered for a prize.

All these facets must be taken into consideration. Judging is not easy; it is hard work when approached with the proper time and skills necessary.

Scale of Points

The Scale of Points in the Standard of Perfection is a helpful tool for the fancier. It lists each section of the bird and the number of points allotted for each. Judges in the USA and Canada use comparison judging now rather than the historical point system. European shows still use points, but they also limit the maximum number of birds per judge.

One such show in Hanover, Germany puts a limit of eighty birds for each judge. In American shows, judges are sometimes assigned several hundred!

Judges now use the Scale of Points to assess the correct number of points to deduct for each defect. That Scale of Points prevents deducting too many points for a defect.

Show etiquette

I have always been admonished to be a good sport and to congratulate the winner. We have all lost to birds seemingly inferior to our own and we have all won classes where we knew our entries were not as good as others. I have always enjoyed the compliments of a fellow breeder-exhibitor whom I respect.

It means far more to me to have a person like that compliment my entries than whether or not I win the class. Not all exhibitors share that opinion and are so highly competitive that words of congratulations choke in their throats rather than being spoken. Shame on them!

“There’s a fine line between dedication and stupidity,” some say. Those of us who schlep birds and all the necessary paraphernalia to show after show cross that line all too often! We have to breed, hatch, rear, and tend our flocks every day in order to have birds in proper condition to enter.

An honest win on a bird we bred and raised ourselves is indeed an achievement of which we can be proud.

I find it enjoyable to observe the deliberation for class and show champions. The judges go together around Champion Row and scrutinize each Best bird, truly nit-picking at its finest!

As a judge, I welcome exhibitors who stand in the row behind where I am working, so long as they do not talk. Once, a judge who finished his challenging and highly-competitive class walked away and said to observers, “Read ‘em and weep; I did my best.”

Midst laurels bestowed

As an exhibitor, I have always enjoyed friendly competition. I remember teasing fellow exhibitors after a good, hot class was placed, “Congratulations! Perhaps I’ll get you next time!” That type of joshing is fun and meant in a friendly and positive manner.

After all is said and done, do we not take pride in our birds, whether or not we won that day? Are we not inspired to go home, take stock of our breeding intentions and make a personal vow to get better next time? I always did just that.

Taking pride in one’s honesty, integrity, and in one’s entries are a “must” for anyone who exhibits. We must learn to be gracious losers, since we all do more losing than winning!

Tags:Plain Talk

Chicken Whisperer is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.