Mama, Where Do Eggs Come From?

An adventure from ovary to vent

In the talk about the birds and the bees, the humble chicken (although a bird) seems to get ignored in this conversation.

From a practical perspective, how the hen makes her eggs is essential toward understanding and recognizing problems with their reproductive system.

Usually hens have problems such as shell-less eggs, being egg bound, and double yolkers when they are just starting to lay eggs, and when they are much older.

To help you understand how problems like this can be managed, let’s go over the basic reproductive tract of a female chicken and link that to how table eggs (aka the eggs that we eat) and fertilized eggs (aka the eggs that eventually hatch into a baby chick) are made.

Where it all starts—the ovary

Astute readers will notice that we wrote “ovary” and not “ovaries.” Unlike most animals that have two ovaries and oviducts (the tube attached to the ovary), birds only have a left ovary and left oviduct. While no one knows why this is so, the majority of adaptations that define birds and allow them to fly (feathers, hollow bones, and lack of teeth), are focused on making birds light.

In other words, two fully developed ovaries are heavier than one fully developed ovary.

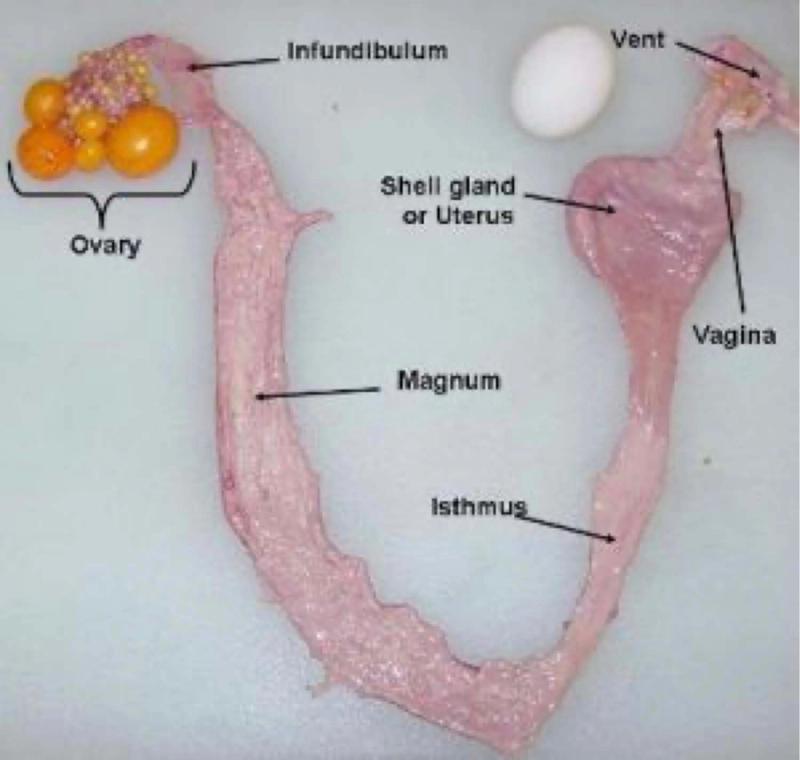

The fully developed left ovary is a cluster of sacs much like a bunch of grapes (Figure 1). When a chick is born, they already have several thousand ova—all they will have for the rest of their lives.

Each of these ova can theoretically develop into a table egg for eating or a fertilized egg that can hatch into a chick.

Once a cute baby chick becomes an adult laying hen at around 18-20 weeks of age, a few yolks at a time increase in size (Figure 1). Once they get big enough, one ova or yolk is released from the ovary and goes on its magical journey through the oviduct.

And here we have two optional outcomes.

Option A: I want eggs for an omelet!

Once the yolk is large enough, it is released from the ovary via a process called ovulation. The released yolk is then picked up by the part of the oviduct closest to the ovary called the infundibulum (or funnel) (Figure 1).

The muscular infundibulum grabs the released yolk and holds it for around 15 minutes. The yolk then passes to the magnum where the thick egg white (or albumin) is added around the yolk for the next 3 hours. The yolk and white now travel to the isthmus where the inner and outer shell membranes form for approximately one hour.

Next, the egg goes to the shell gland (or uterus) where the shell is formed around the egg. This process takes about 20 hours and utilizes up to 10% of all the calcium in the hen’s body! The shell gland is also where the pigment is added that makes the eggs blue, brown, speckled, etc.

Finally, the last part of the oviduct is the vagina which doesn’t play a part in egg formation but does two important things:

- This is where the bloom or cuticle is added to the shell. The cuticle has some anti-bacterial properties which help mitigate (not eliminate) bacterial growth.

- The vagina helps push the egg out of the body in such a way as to prevent fecal material from getting on the egg shell—a pretty amazing trick since the cloaca is also the orifice that poop leaves from!

To finish off this adventure, you pick up the egg and make your omelet!

Option B: Fertilization

First the obvious: for a hen to lay a fertilized egg, she needs a rooster.

Mating is a funny and short process for chickens, taking just a few seconds. The rooster circles the hen, making a big “hubbub” and eventually mounts the hen, biting down on the feathers of the hen’s head and neck for balance. Chicken sex: The rooster’s papilla (the equivalent of a penis and is in their cloaca) delivers the sperm to the hen’s cloaca and away the sperm swims.

The sperm will fertilize the yolk in the infundibulum.

Since the yolk is only in the infundibulum for around 15 minutes, hens have “sperm host glands” where sperm can be stored for up to 2 weeks!

Stored sperm can be delivered to the yolk in order to allow for fertilization even if the rooster has delivered sperm when there is no yolk in the infundibulum!

The rest of the journey for the fertilized egg is identical to Option A.

However, the egg will not develop until certain conditions are met, the most important being heat. Hens will brood their eggs (fertilized or not)—an incubator simulates that process.

Yes, things can go wrong

Sometimes irregularities occur in egg development.

Occasionally a hen lays a shell-less egg. In this case the egg bypasses the shell gland and or the shell is not completely deposited. This could be the result of a nutrition problem (not enough calcium), infectious diseases such as Infectious Bronchitis virus, or simply due to age (young hens and old hens). It can also be associated with stress.

Egg yolk peritonitis (EYP) is a syndrome where the infundibulum doesn’t catch the yolk and it ends up in the abdomen causing inflammation and infection. Unfortunately, this is a life-threatening problem (even with treatment) primarily due to the resulting infection. The best way to prevent EYP is via good management and nutrition.

With proper nutrition, biosecurity, and husbandry, we can help ensure that our chickens have a happy and healthy reproductive life-span.

Tags:Pitesky's Poultry

Chicken Whisperer is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.